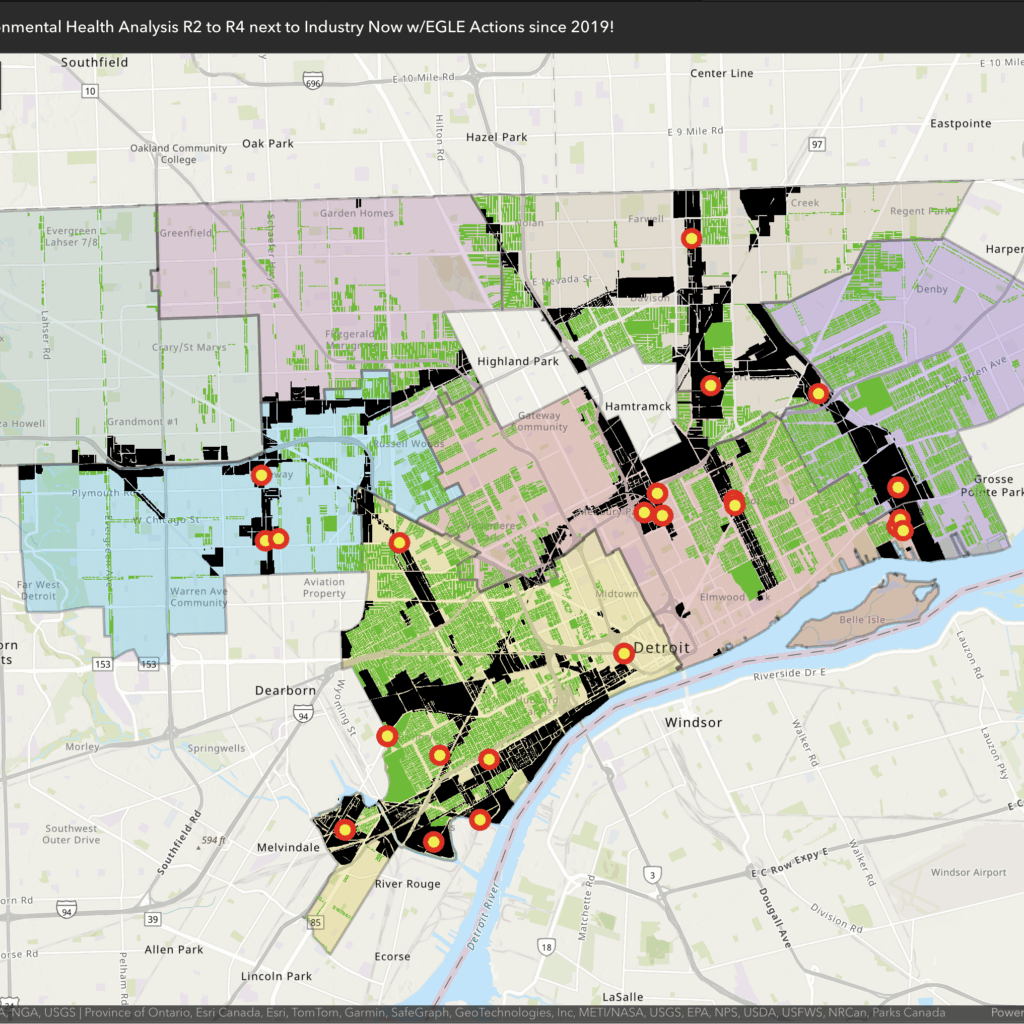

Updated with FOIA’d EGLE Violation data Nov 9, 2025 – The map shows R2 residential zones in green and industrial zones in black, revealing heavy overlap in Districts 4, 5, and 6, where family homes sit beside factories and truck routes. The proposed “Let’s Build More Housing, Detroit” ordinance would make multifamily housing a by-right use in R2 areas, allowing higher-density development without additional review. Records from EGLE show dozens of environmental violations since 2019 across industrial corridors, including dust, odor, and air-quality complaints near occupied homes. In neighborhoods already burdened by emissions and truck traffic, adding more residents could expand the population living within zones of industrial exposure and complicate oversight and accountability for both developers and regulators. Before expanding by-right housing in these areas, Detroit must weigh environmental health and ensure growth does not deepen existing harm. https://arcg.is/GbrWa0

NOTE: A public hearing has yet to be set for these proposed changes. Council contact info and links/details to join meetings to make public comment: https://detroitmi.gov/government/city-council

Key Findings

- Detroit’s proposed “Let’s Build More Housing, Detroit” ordinance is a citywide text change that would allow three- and four-unit homes by right in R2 zones.

- Many R2 areas—especially in Districts 4, 5, and 6—sit within 1,000 feet of M1–M4 industrial corridors.

- From 2019–2024, Detroit logged 1,000+ air-quality complaints in these same neighborhoods; multiple violations are common, Stellantis, Aevitas, US Ecology and other sites.

- Federal oversight has weakened, and local enforcement remains limited.

- Best practice: a 300-foot residential buffer and coordination with EGLE before new multifamily permits are issued.

- Without safeguards, upzoning could increase exposure in communities already living with industrial pollution.

Detroit’s proposed “Let’s Build More Housing, Detroit” ordinance would amend the zoning code to allow three- and four-unit homes by right in R2 residential districts that currently permit only single- and two-family dwellings. It’s a text change, not a map change — meaning the zoning boundaries stay the same, but what’s allowed inside them expands across every R2 neighborhood citywide.

The intent is straightforward: to make it easier to build and close Detroit’s housing gaps. But residents across the city have raised valid concerns—about the loss of local control over what gets built next door, the potential to deepen gentrification and displacement, and the limited opportunities for meaningful community input. These critiques matter. They reflect long-standing tensions around who benefits from “growth” and who bears its costs.

This environmental analysis adds another layer to that discussion, recognizing that land use and air quality are inseparable. Many R2 neighborhoods border active manufacturing corridors where factories, truck yards, and scrap operations are part of daily life. That proximity makes this proposed text change more than a technical adjustment—it’s an environmental decision, too.

Where R2 Meets Industry

Across Districts 4, 5, and 6, large stretches of R2 zoning sit within 1,000 feet of M1–M4 manufacturing districts — especially along Mack, Conner, Mt. Elliott, and Jefferson. These corridors include foundries, recyclers, and freight routes that have shaped the city’s industrial landscape for generations.

Between 2019 and 2024, Detroit logged more than 1,000 odor, smoke, and dust complaints, mostly from these same neighborhoods. EGLE and EPA ECHO data confirm repeated violations of Michigan Rule 901(b) for visible emissions and fugitive dust. EPA EJScreen 2024 places many of these tracts in the 90th percentile nationwide for diesel and air-toxics exposure.

The R2 amendment wouldn’t increase emissions — but it would put more people in the middle of them, allowing higher-density housing in corridors that already carry Detroit’s heaviest environmental load.

Enforcement That Rarely Resolves

Detroit’s industrial record tells its own story. Violations often end with minor fines that go to the state’s general fund or long compliance schedules that don’t fix the problem. Residents continue to report dust and odors years after violation cases are closed. Building more housing into those same zones adds residents while the underlying conditions remain the same. This isn’t about opposing housing. It’s about timing — development moving forward faster than environmental correction.

The Policy Gap

Federal and state rules limit what industry can emit, but they don’t control where people live in relation to it. The Clean Air Act still defines national standards, but its reach has been narrowed by recent court decisions. Michigan’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (Part 55) lets EGLE regulate emissions, not land use.

That responsibility rests with the city. Under the Michigan Zoning Enabling Act, Detroit must plan for public health, safety, and welfare. The proposed R2 change doesn’t violate that duty — but it doesn’t meet it, either. It expands residential use in places already proven to have air-quality issues, without any review or local safeguard in place.

Lessons from Other Cities

Detroit isn’t alone in facing the tension between new housing and long-standing industry. Other cities that moved forward with similar upzoning have seen what happens when environmental review comes too late. In Chicago’s Little Village, a smokestack implosion in 2020 blanketed nearby homes in dust after industrial land was rezoned for mixed use, with only minor fines issued afterward. In Houston’s Fifth Ward, homes built near a contaminated rail yard later showed elevated cancer rates, while cleanup was delayed by zoning disputes. And in Minneapolis, a state court temporarily halted the city’s 2040 Plan after finding no environmental review had been completed. Together, these examples show that when zoning expands housing into industrial corridors without health checks or buffer standards, residents—not polluters—end up carrying the risk.

What the City Could Do

Detroit can still move forward — but do it responsibly. By considering these risks and pausing these zoning changes, the city could increase future protections, and:

- Coordinate with EGLE before approving new R2 multi-unit housing within 1,000 feet of M1–M4 zones or heavy truck routes, reviewing recent complaint and violation data.

- Adopt a 300-foot buffer standard, using tree lines, fencing, or building orientation to cut down dust, diesel, and noise.

- Require disclosure of active air-quality violations during permitting, so both developers and residents know existing conditions.

- Map air-quality and complaint data directly into zoning analysis, so density decisions reflect real environmental conditions.

These steps are practical, fully within Detroit’s authority, and based on data the city already has. They wouldn’t slow housing — they’d make sure it’s built safely.

Notes: Resident Rights and Neighborhood Exposure

Detroit’s neighborhoods sit close to long-standing industrial corridors—especially along Conner, Mack, St. Jean, Mt. Elliott, and Southwest Detroit. The proposed changes would make it easier to build new housing in or next to these areas. That creates new opportunities but also new risks.

Reduced Protection from Industrial Impacts

If housing and industry are listed as compatible in the zoning code, residents living near factories, truck yards, or recyclers would have less ability to challenge odors, dust, or noise. When people complain about pollution, companies can point to the zoning map and argue that the use is allowed there—making it harder for the City or the state to act.

Fewer Health Safeguards

State environmental rules—like Michigan’s Air Pollution Control standards—treat homes and schools as “sensitive receptors.” If zoning encourages new housing right next to industry, regulators may assume residents chose to live there and could give lower priority to future enforcement or permit limits.

This shift can make it easier for existing industries to renew or expand operations without added review.

Everyday Exposure

People moving into new by-right units along busy truck corridors could experience more diesel exhaust, vibration, and noise. Without environmental or health screening, those risks aren’t measured or reduced before construction begins—putting the cost of exposure on residents instead of operators.

Limited Public Input

Because these new uses would be by right, they skip public hearings and appeals. That means neighbors would not be notified or consulted before projects are approved—removing a step that often identify pollution concerns early.

Notes: Michigan Law and City Responsibility

Several state laws require Detroit to consider health and safety when it changes zoning:

| Law | Purpose | Why It Matters Now |

|---|---|---|

| NREPA Part 17 (MEPA) | Prevent government actions that cause “unreasonable environmental impairment.” | Allowing new homes next to known pollution sources could violate this principle if impacts rise. |

| Public Health Code §333.2451 | Requires local governments to correct conditions that threaten public health. | More housing near industry means more health complaints for the City to address. |

| Air Pollution Control (Part 55) | Separates emission sources and “sensitive receptors.” | New residential receptors inside industrial buffers make enforcement harder. |

| Michigan Zoning Enabling Act (MZEA) | Requires zoning to promote public health, safety, and welfare. | A review of environmental impacts would help meet this requirement. |

Together, these laws show that Detroit must look at health and cumulative exposure before finalizing major zoning changes.

Notes: National Examples

Chicago, Illinois (2020 – Hilco Redevelopment)

After Chicago rezoned a former coal-plant site for warehouses, a smokestack implosion blanketed Little Village in dust.

Because the area had been reclassified as “mixed use,” regulators imposed minimal fines.

Residents reported lingering respiratory problems.

Chicago Tribune (2020)

Lesson: Rezoning industrial land without health review can shift liability from polluters to residents.

Houston, Texas (2021 – Union Pacific Creosote Site)

In Houston’s Fifth Ward, a rail-yard released toxic creosote for decades.

After nearby parcels were rezoned for housing, the company argued that new residents had “come to the nuisance,” limiting cleanup liability.

EPA later confirmed elevated cancer rates.

EPA Region 6 Record (2021)

Lesson: Zoning that mixes housing and heavy industry weakens residents’ rights to seek protection later.

Los Angeles, California (2017 – Boyle Heights Corridor)

After LA created its “Clean Up Green Up” zones, some recyclers claimed “non-conforming use” rights to avoid stricter air rules.

Los Angeles Times (2017)

Lesson: Even well-intended reforms can backfire if zoning language gives polluters new loopholes.

Minneapolis, Minnesota (2023 – 2040 Plan Upzoning)

Residents sued, saying the city failed to study environmental effects of its citywide upzoning.

A state court agreed and temporarily stopped the plan.

Star Tribune (2023)

Lesson: Cities must analyze environmental impacts before approving sweeping zoning changes.

Providence, Rhode Island (2022 – Port Expansion)

Zoning that allowed more mixed industrial use near the port increased truck traffic through residential streets.

Residents filed a complaint, and EPA required new mitigation steps.

Providence Journal (2022)

Lesson: Local zoning can trigger federal review when it raises cumulative pollution burdens.

Notes: What the Data Suggest

Detroit’s proposed ordinance would not rezone industrial land, but it would invite more residential development into areas already affected by heavy use and traffic. That change could:

- Increase the number of people exposed to diesel and industrial emissions.

- Make it harder to enforce existing pollution rules.

- Raise property values in high-burden areas before affordable housing is built, increasing displacement risk.

These are manageable risks—but only if tools are added that recognize them.

Detroit is proposing to update its zoning for the first time in decades. The goal—more housing and simpler rules—is widely shared. But when new homes move closer to long-standing industry, the City must protect people’s right to clean air, quiet homes, and stable neighborhoods. There has not been enough consideration of these environmental health concerns in the planning and community engagement around these sweeping changes. By adding clear buffers, short health reviews, and transparency measures in future planning and engagement, the Let’s Build More Housing ordinance could deliver not only more homes, but also healthier, safer neighborhoods—for everyone.

Sources and References

Ordinance and Local Context

- City of Detroit – “Let’s Build More Housing, Detroit” Ordinance (2025 draft)

https://detroitmi.gov/government/mayors-office/zoning-ordinance-build-more-housing

Official text amendment to Chapter 50 (Zoning), detailing by-right changes in R2, R3, and related districts. - City of Detroit Zoning Code, Chapter 50

https://library.municode.com/mi/detroit/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIIICOOR_APXAZOCO_CH50ZOOR

Full zoning ordinance text, including sections §50-8-44 (R2 District) and §50-14 (Parking Requirements).

Federal and State Law

- Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. § 7401 et seq.)

https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview

Primary U.S. law regulating air emissions; includes NAAQS standards and “sensitive receptor” language used in air-quality planning. - Michigan Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (NREPA), Part 55 – Air Pollution Control

https://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(…))/mileg.aspx?page=getobject&objectname=mcl-324-5501

Authorizes EGLE to regulate and enforce air contaminants that “may endanger human health or welfare.” - Michigan Zoning Enabling Act (Public Act 110 of 2006)

https://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(…))/mileg.aspx?page=GetObject&objectname=mcl-Act-110-of-2006

Defines the purpose of zoning to promote “public health, safety, and general welfare.”

Enforcement, Violations, and Environmental Data

- Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) – Air Quality Division Violation Notices & Enforcement

https://www.michigan.gov/egle/about/organization/air-quality

Repository of Rule 901(b) violations and facility enforcement actions statewide. - EPA ECHO (Enforcement and Compliance History Online)

https://echo.epa.gov/

Database showing facility-level inspections, violations, and enforcement outcomes across Detroit. - Detroit Environmental Enforcement Data (Public Records Portal)

https://data.detroitmi.gov/

City complaint and violation logs, including “Air Quality” and “Nuisance Odor” datasets (2019–2024). - EPA EJScreen 2024 – Environmental Justice Mapping Tool

https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen

Environmental and demographic indicators; Detroit east- and southwest-side tracts rank above 90th percentile for diesel particulate and air toxics.

Planning and Health Standards

Chicago Tribune – Little Village Dust Incident (April 2020)

https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/environment/ct-met-hilco-demolition-little-village-air-pollution-20200411-5lrb…

Documented air-quality event following industrial-to-mixed-use redevelopment.

U.S. EPA – Air Quality and Land Use Handbook: “A Community Guide to Air Quality and Land Use Planning”

https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/air-quality-and-land-use-handbook

Recommends minimum 300-foot separation between residences and truck routes or stationary sources.

City of Detroit Green Infrastructure Plan (2016)

https://detroitmi.gov/departments/office-sustainability

References 300-foot best-practice buffers for land-use compatibility near industrial corridors.

American Planning Association – Industrial Land Use Compatibility Guidelines (2019)

https://planning.org/

Cites 300-foot residential setback as baseline for mitigating particulate exposure.

Minneapolis 2040 Environmental Review Case

https://www.startribune.com/judge-pauses-minneapolis-2040-plan-over-environmental-review/600271301/

Example of a citywide upzoning halted for lack of environmental analysis.